Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Dis Manibus (The Roma Widow), Oil on Canvas 1874, Museo de Arte, de Ponce, Puerto Rico

Dis Manibus (The Roman Widow), is not one of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s better known works. Through the vicissitudes of history, the lovely painting of the young, bereaved woman, originally commissioned by the artist’s patron the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland, has ended up almost the other side of the world from its London origins, as part of the wonderful collections of the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, where it is in the same collection is Frederic Leighton’s stunning Flaming June (1895). It has often struck me that Rossetti’s depiction of a delicate, almost ghostly, pale widow has, for too long, been hiding in the shadows of Leighton’s solar blaze.

Frederic Leighton, Flaming June, Oil on Canvas 1895, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico.

The painting depicts a widow of ancient Rome sitting beside the cinerary urn that contains her husband’s remains. The urn is inscribed: DÎS MANIBUS/ L. AELIO AQUINO/ MARITO CARISSIMO/ PAPIRIA GEMINA / FECIT/ AVE DOMINE. VALE DOMINE (To the deities of the underworld: Papira Gemina has made this for her dearest husband Lucius Aelius Aquinas: hail master, and farewell master). The inscription on the urn is taken from a Roman urn in Rossetti’s collection (Rossetti was an avid collector of all manner of antique objects) . The model for this painting is Alexa Wilding.

The widow is playing an elegy to ‘Dîs Manibus‘, the ‘Divine Manes‘. The Manes were believed to be ‘ghost-gods’- chthonic (underworld) deities that represented the souls of deceased loved ones. She plays on two harps, one with each hand (Rossetti took the imagery of the harps straight from wall paintings at Pompeii), a convention in classical funerary imagery. The circular silver-white girdle that hangs on the urn symbolises her enduring love for her dead husband. The pink old-fashioned and wild roses are the flowers of Venus, the goddess of erotic love.

Although portraying ancient rites, the comparison between these specific rites and the growing belief in Spiritualism of the second half of the nineteenth century cannot be overlooked. As has been much discussed elsewhere, Rossetti became involved in Spiritualism and attended, and held, séances, an interest which may have been, at least in part, a response to the untimely death of his wife Elizabeth Siddal in 1862. However, this theme is a constant throughout Rossetti’s career, initially inspired by his fascination Dante Alighieri’s immortalisation in literary form of his enduring love for Beatrice.

Works such as the poem and painting The Blessed Damozel (the poem was first published in 1850 and revised in 1856 & 1873, the painting was created 1875-8) and particularly the Willowwood Sonnet sequence (1868) are attempts to represent the endurance of love beyond death, and the plaintive longing of the living for the dead. And, as with Willowwood where the narrator encounters love in the form of music as he tries to reach out into the otherworld of lost love, here in Dîs Manibus we are also privy to the heady combination of love and music as the grieving widow uses both to communicate with her lost love in the underworld. I don’t believe that it is remotely fanciful to conclude that Rossetti saw his art and poetry throughout his career as an attempt not only to represent, but as a form of communion with, love in all of its forms, be they lost, real, or unobtainable.

The Blessed Damozel, Oil on Canvas, 1871-8, Fogg Museum, Harvard University

The more I have thought about Dîs Manibus, the more it has fascinated me. Rossetti devoted much of the 1870s to painting his enigmatic three-quarter length portraits of women influenced, in part, by Venetian Renaissance portraiture. Dis Manibus certainly fits into that category, but the subject matter is unusual as it is a Neoclassical one of the kind more usually seen in the work of his near-contemporaries Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Albert Moore. At the time that Dîs Manibus was painted, Alma-Tadema was achieving remarkable success by featuring authentic details in his imagined depictions of ancient Rome, and he was lauded for his subtle use of colour, particularly shades of white.

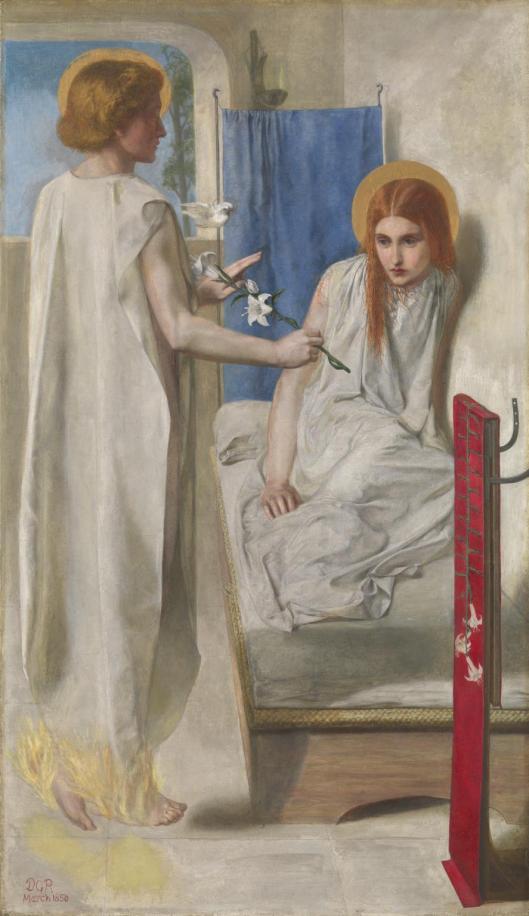

It has been suggested that with his experimentation with white and neoclassical themes in Dîs Manibus , Rossetti was rising to the challenge of Alma Tadema’s success. However, Rossetti was also experimenting with the use of whites as early as 1849-50 with Ecce Ancilla Domini! in which white is the dominant colour, an incredibly radical undertaking in mid-nineteenth century British painting.

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation) Oil on Canvas, 1849-50 Tate

Rossetti’s early experimentation was repeated again in the 1860s with Lady Lilith, as he layered different tints of the colour – or non-colour – to stunning effect against a dark background.

Lady Lilith, Oil on Canvas (1866-68, altered 1872-3), Delaware Art Museum

In Dîs Manibus, the use of white serves to remind us of the absence of the woman’s departed husband. Her pale wraith-like face and drapery gives her an unworldly quality, and here, we sense, is someone not quite living in this world, nor the next. The roses add to the pale, subtle tonality and, as the symbols of Venus, signify the endurance of love, even after death.

The medallion frame was designed by Rossetti and made by Foord and Dickinson. For a discussion of this see Lynn Roberts’ excellent Frame Blog https://theframeblog.com/tag/millais/

Thank you, I found this interesting and enlightening.

LikeLike

Many thanks for your comment- I’m glad you enjoyed the post!

LikeLike